Pronatal Policy Essay #1: Favoring the Young over the Old

This essay is part of a series of policy essays exploring ways to raise birthrates.

If you ask young people why they don’t have children, financial considerations are near the top of the list. In a 2024 Pew poll, 36% of respondents under 50 gave “Can’t afford to raise a child” as a major reason they are childless.

The Wealth and Fertility Paradox

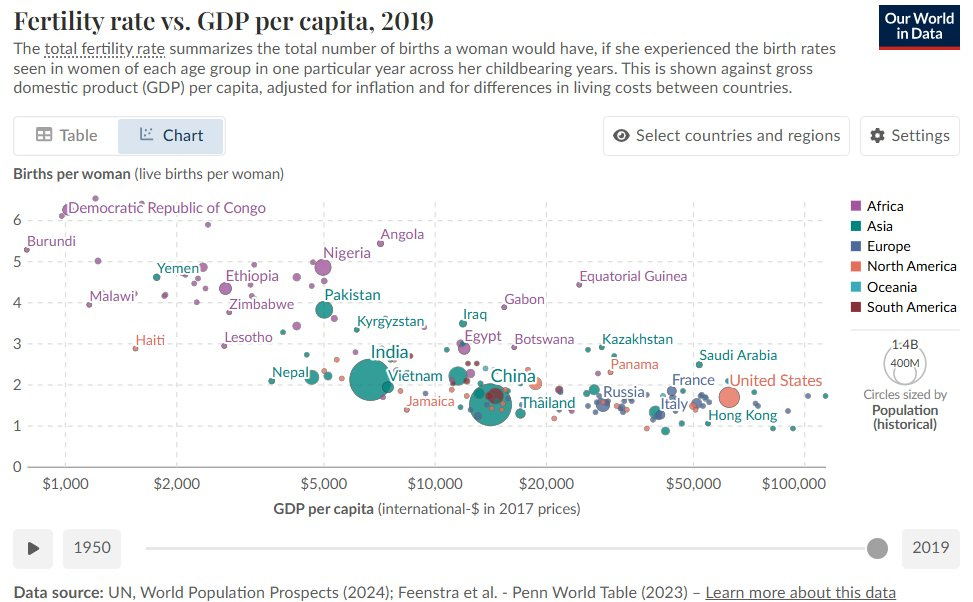

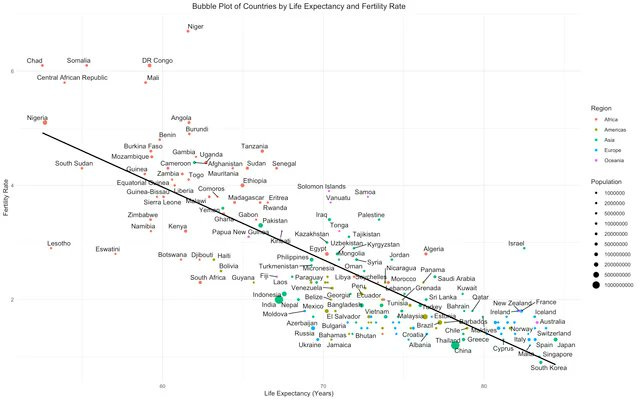

Most people know about the wealth and fertility paradox. As countries get richer, fertility goes down, so that the richest countries have some of the lowest fertility rates while the poorest countries have the highest fertility rates.

Not only that, but as countries get richer their fertility rates plummet. South Korea’s GDP per capita went from $158 in 1960 to $36,000 today, while fertility went from 6 births per woman to just 0.75.

So low birthrates can’t really be about money, right? Well, when you ask young South Koreans what is keeping them from having children, money comes up over and over, even more than it does for Americans.

What’s going on?

It’s all relative, and young people are relatively poor

Why do young people keep saying they can’t afford kids, when in reality society is richer than ever before? Are they just spoiled?

Part of it is down to priorities. Young people are choosing to emphasize careers first. But the truth is that young people are at the bottom of the heap, money-wise. One of the most miserable experiences in the world is feeling low-status, and in our world where status is tied to money, a lot of young people are feeling the burn.

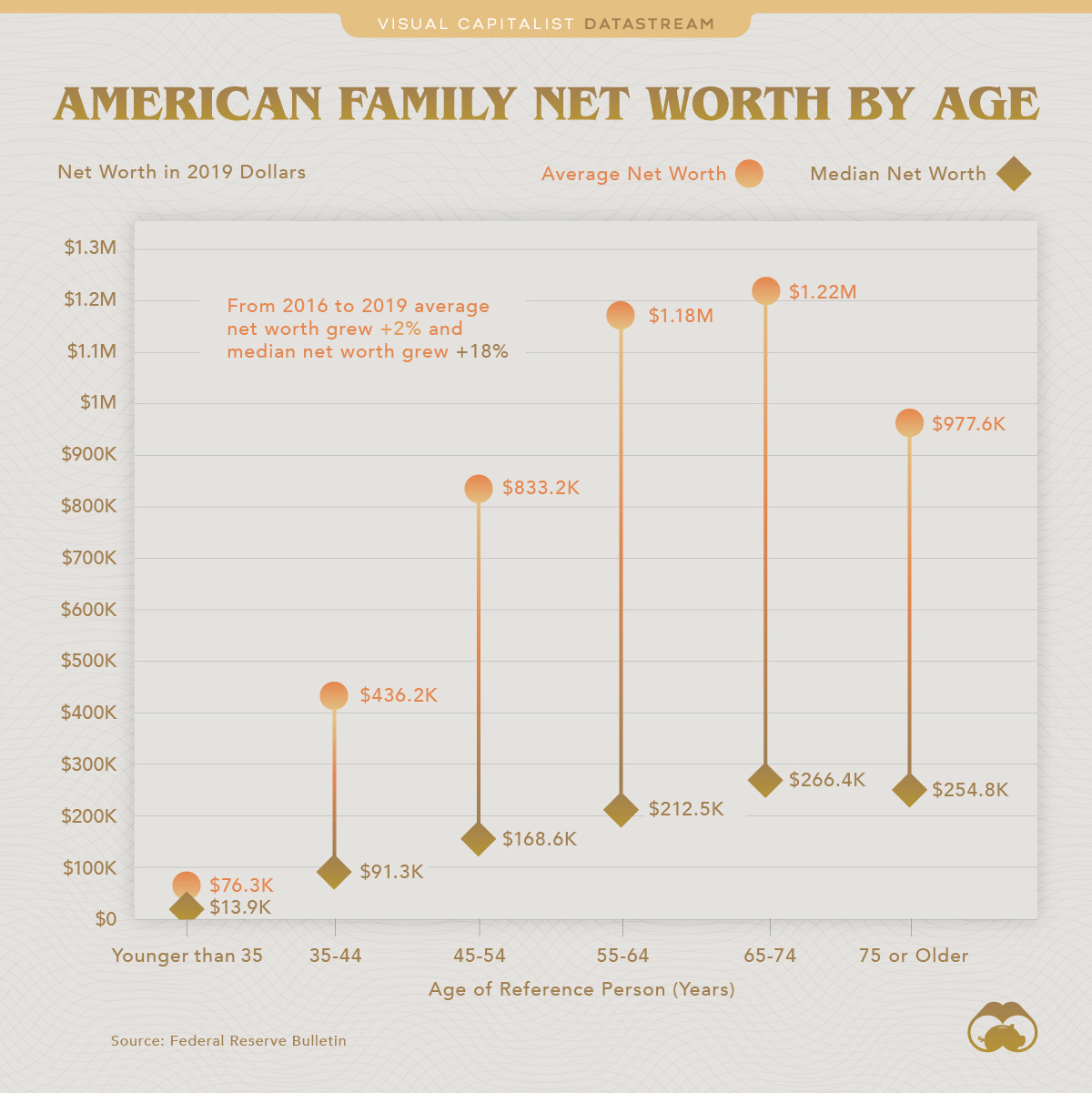

Most people have very little wealth until their late 30s, and then they hit their stride in their 40s.

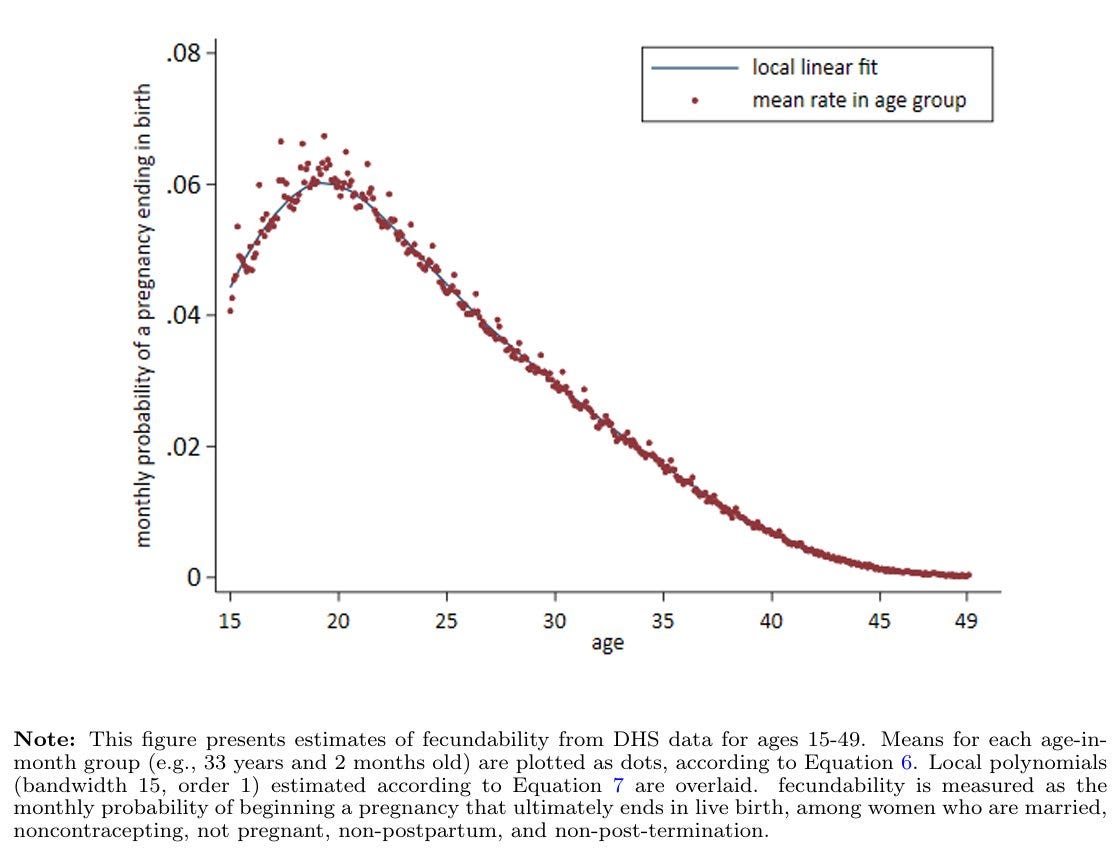

But that is a big problem for birthrates when ‘fecundability’ (how easy it is to get pregnant) is high in the 20s but is much lower after 35.

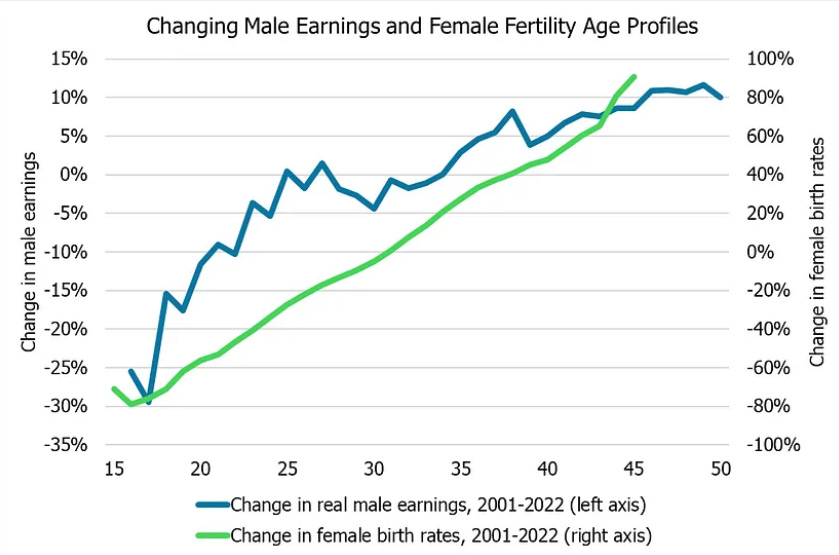

Haven’t young people always been relatively poor? No, not like today. Demographer Lyman Stone looked at the change in male earnings from 2001 to 2022 at across ages and looked at what happened to female fertility at from 2001 to 2022 for these same ages.

Young men’s income has been declining in the 20s, and this has been associated with lower birthrates for women their most fertile years. The relative status of young men is dropping, making them less attractive as partners. Men are doing better in their late 30s and 40s, but by that time, the fertility window is closing. (This age comparison works because men tend to partner with women who are about the same age.)

Young People Are Hitting Milestones Later than Ever

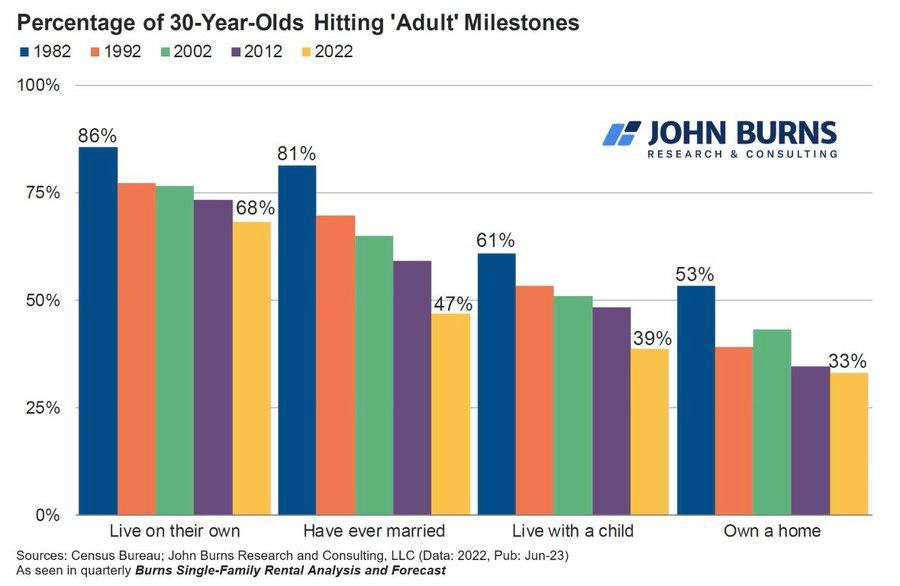

Amid this delayed financial success, young people are hitting the milestones of life later than ever. Decade by decade, a smaller and smaller share of young adults have achieved the big things (live on their own, have ever married, live with a child, own a home) by age 30.

If only a third of thirty-year-olds manage to own a home and another third still live with their parents, that will wreck birthrates.

Empty Nesters Dominate the Supply of Single-Family Homes

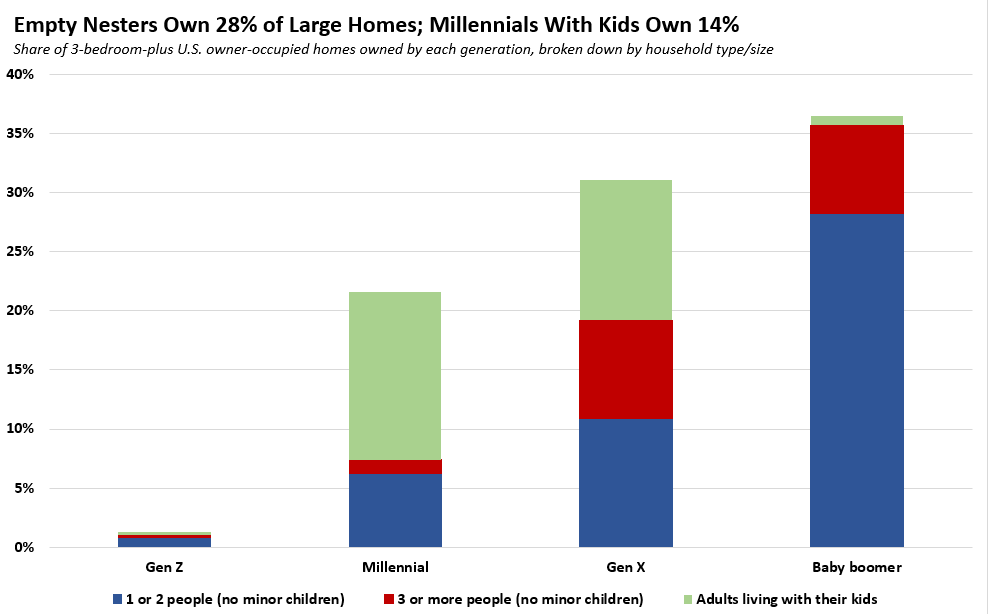

A study published in 2024 by real estate giant Redfin found something remarkable. Of homes most suitable for families (3 or more bedrooms) Millennials (who were 28 to 43 in 2024) and Gen Z (up to age 27) owned just 22% of them.

That means that people who were older than 44 in 2024 owned 78% of the 3+ bedroom houses in America! Most people in their childbearing years are stuck in something small, if they even live on their own at all.

If you think the norm of 3 bedrooms for family is just a modern convention one can dispense with, consider this: Child Protective Services typically have guidelines that there should be separate bedrooms for opposite-sex children over five years old, and children shouldn’t share a room with an adult unless they are an infant. Rental companies also impose strict occupancy limits.

That means that to have just two kids, a boy and a girl, two bedrooms will not do. Millennials don’t merely feel bad about not being able to afford a three-bedroom starter home. It is actually a big risk to have a family without one.

But there aren’t enough family-sized houses to go around, and people who are done with kids are dominating the market.

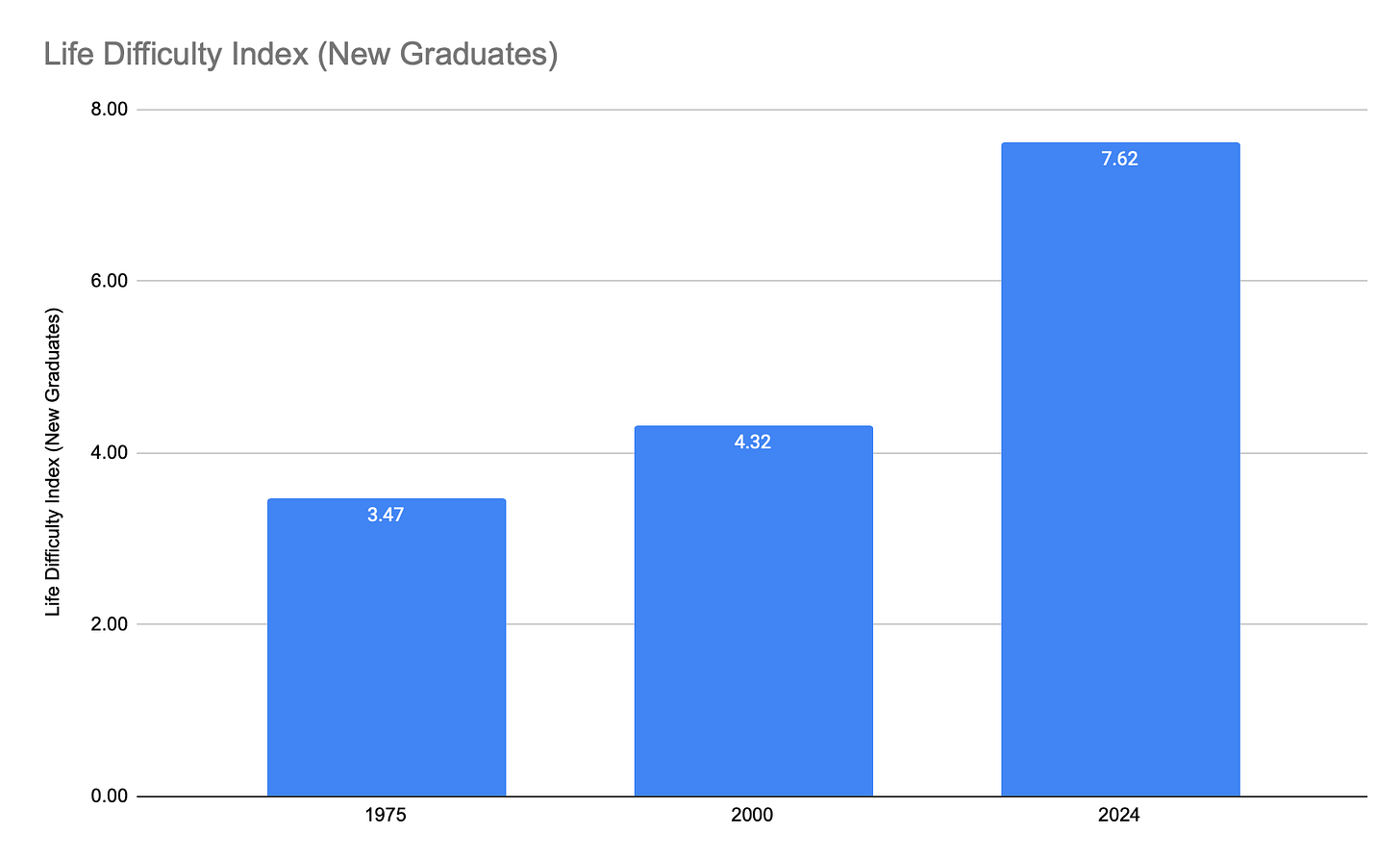

We can measure just how hard things are for young people getting started. Writer Tom Owens created the ‘Life Difficulty Index.’ It measures how hard it is for a new graduate with the median income to buy a median house and an average car.

The cost of a median house and a median car has risen 2.2 times faster than incomes for young graduates over fifty years. So, for young people starting out it is indeed a lot harder than it was for their parents and grandparents.

Retirees aren’t even using their savings

Everyone knows that you have to save up while you are working because you will need to spend that money in retirement. That’s what every financial advisor will tell you, and that’s how all the retirement calculators work.

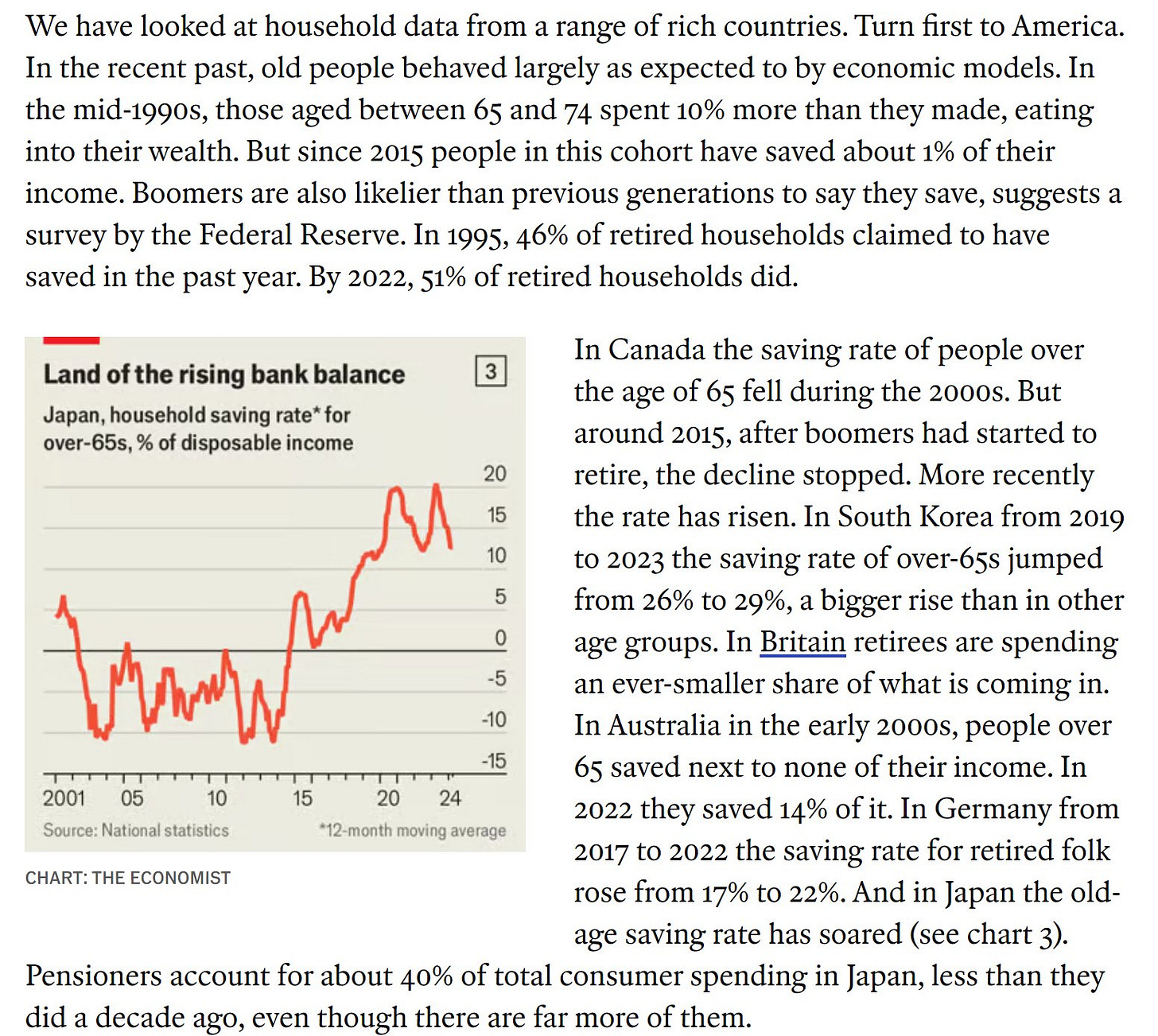

Well, something incredible has happened in rich countries. People above age 65 have come to have a positive savings rate, The Economist found.

This is the opposite of what most people expect. On average, those over 65 in rich countries aren’t even drawing down their savings but are still adding to their savings every year!

Keep in mind, this is even before all the asset appreciation they have enjoyed in houses, stocks and bonds.

Social spending flows uphill

We’ve seen that across the developed countries, most of the wealth is in the hands of the old.

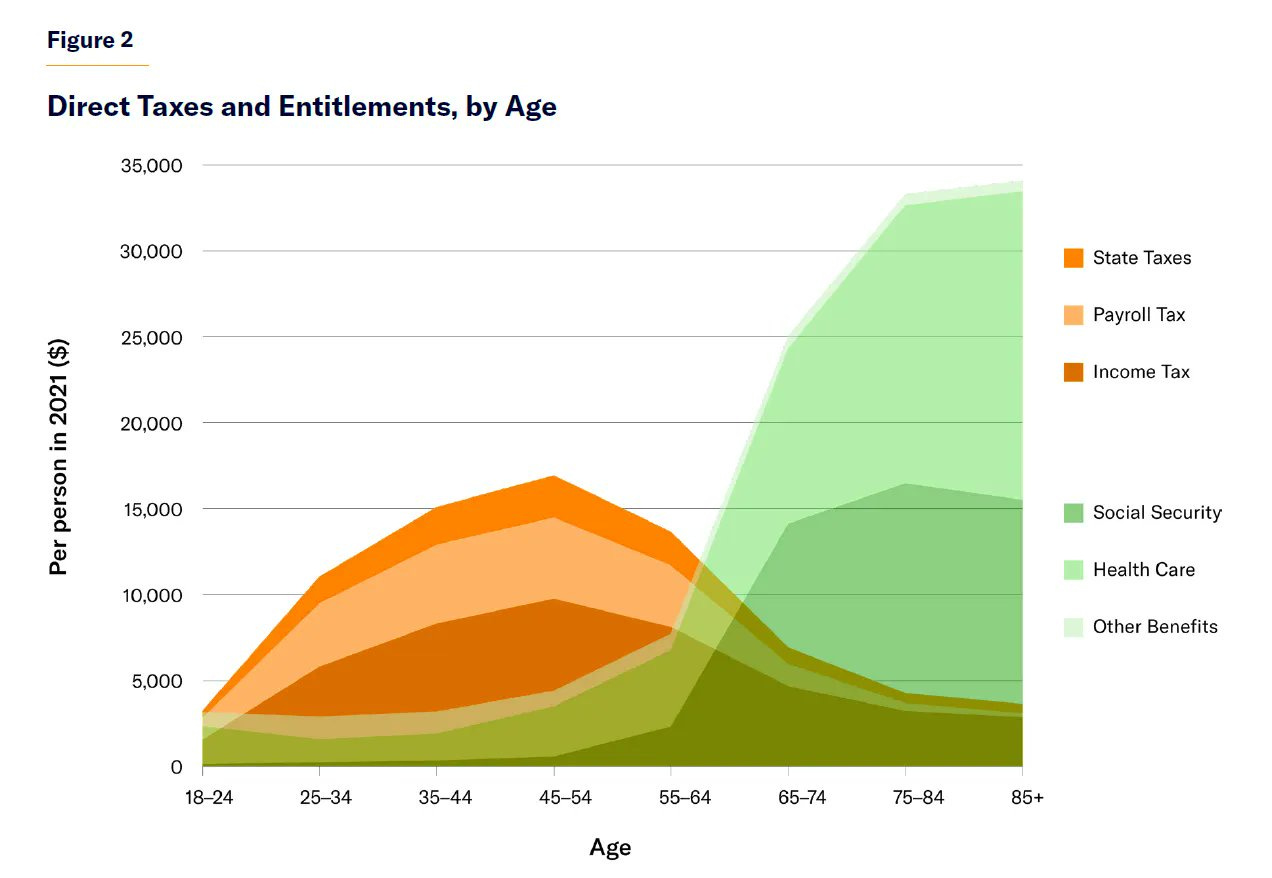

So, what do taxes and spending look like by age?

In short, the money flows uphill from the young and poor to the old and rich. The ones who should be having children are busy struggling to pay their bills while sending big sums to seniors who on average have much more than they do.

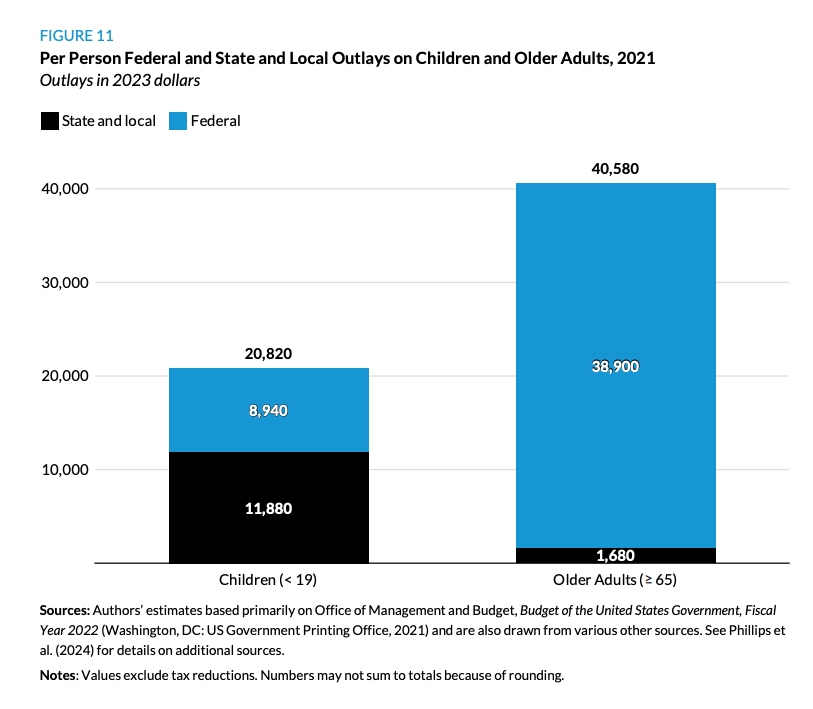

Here is another way of looking at things. Even when you count all spending on education, government still spends twice as much on seniors as on children. At the federal level, the difference is five times.

But parents don’t only shoulder a heavy burden when they are young. They often get fewer benefits when they are old. Consider two older women, one who was childless and had a career and another who stayed home raising a bunch of children who are now productive citizens. Which one qualifies for social security? Only the first woman.

The impact of deficits and inflation

There is one policy that stacks the deck against the young more than any other.

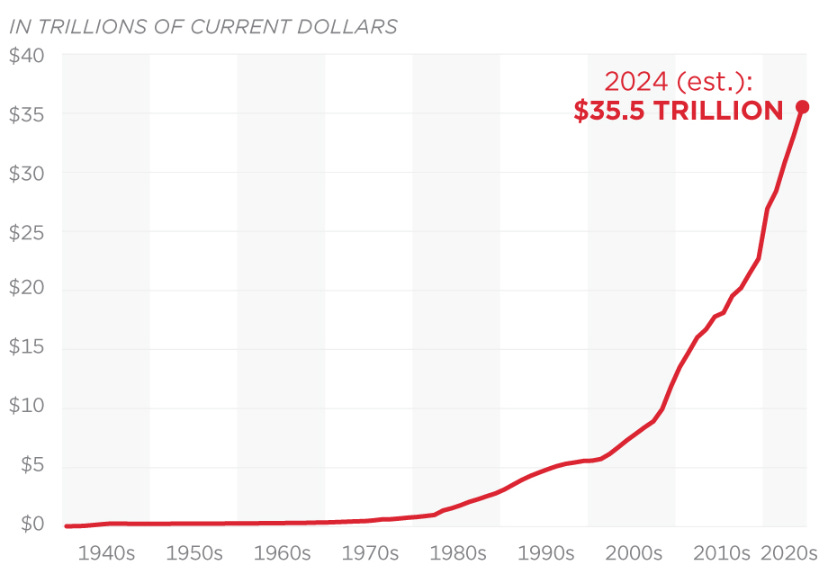

Budget deficits represent a borrowing in the present with debts put off into the future. America’s $35 trillion-dollar national debt means that that there is debt share of about $110,000 for every American.

And birthrates below replacement mean that the share of debt for each worker will be larger still.

But that isn’t the only way that deficits hurt the young. The inflation that results from deficits goes into assets like houses, making them much pricier to young people who haven’t bought in yet.

Meanwhile, the high interest rates needed to fight inflation mean that mortgage payments are far higher than they would otherwise be. Future homebuyers are squeezed by deficits in two different ways.

Seniors meanwhile are insulated from inflation in two big ways. First, the assets they own rise in value with inflation. Second, the benefits they receive are usually indexed to inflation.

Inheritance doesn’t fix the problem

If Baby Boomers have all this wealth, won’t inheritance fix things? Don’t Millennials stand to inherit a fortune?

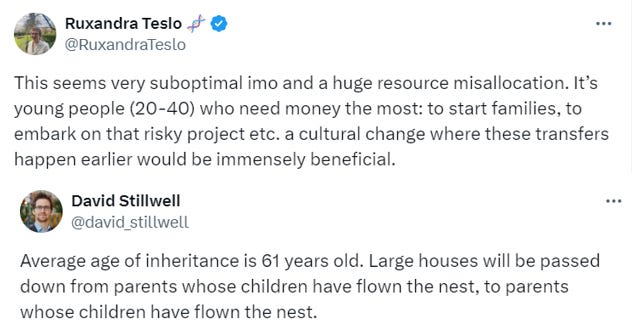

Try not to get too depressed when you learn that the average age of inheritance is 61 years old.

Is the burden of the old causing lower birthrates?

If you plot fertility as a function of life expectancy, the longest-lived countries have the lowest fertility. Of course, life expectancy could just be a stand-in for national wealth.

But what if the numerous elderly of Korea, Japan, Italy and Spain are hurting fertility directly by claiming resources (from houses to social spending to care workers) that might otherwise go to families with children?

Policies to favor the young over the old

Given the extraordinary imbalances we see in favor of the old, especially for scarce resources like houses, it is logical that pronatal policies should favor the young. Here are a few obvious things:

Control deficits and limit debt-financed elderly entitlements. Future generations are doubly burdened, first by the debt itself and the interest that must be paid on it, and then by the pernicious effects of inflation, which make homebuying much harder.

Tilt social spending toward families more than seniors. It defies logic that so much money should flow from young and poor to the old and already rich, but that it how it is in almost every developed country.

Favor property taxes over income taxes. The latter disproportionately hit the young while the former are born by the old who are much wealthier.

Stop exempting seniors from property taxes. The elderly often are given exceptions on property taxes, so they aren’t pressured to move out of their houses. But the elderly often possess homes far larger than they now need, even as those wanting to start families are often confined to tiny apartments. Property taxes would incentivize the old to sell houses to the young, which is good for society in a world of too-low birthrates.

Give parents better retirement income than non-parents. Parents do the hard work of raising up the productive citizens of the future. Yet non-parents, who didn’t contribute to society in that most fundamental way, often get more money in retirement than parents, because they had more years of work outside the home.

Smash the Gerontocracy?

Right now, society tilts hard in favor of the old over the young, at least financially. In most developed countries, people are in the weakest financial position of their lives during the prime childbearing years and are in the strongest financial position of their lives in old age, when they aren’t even working anymore.

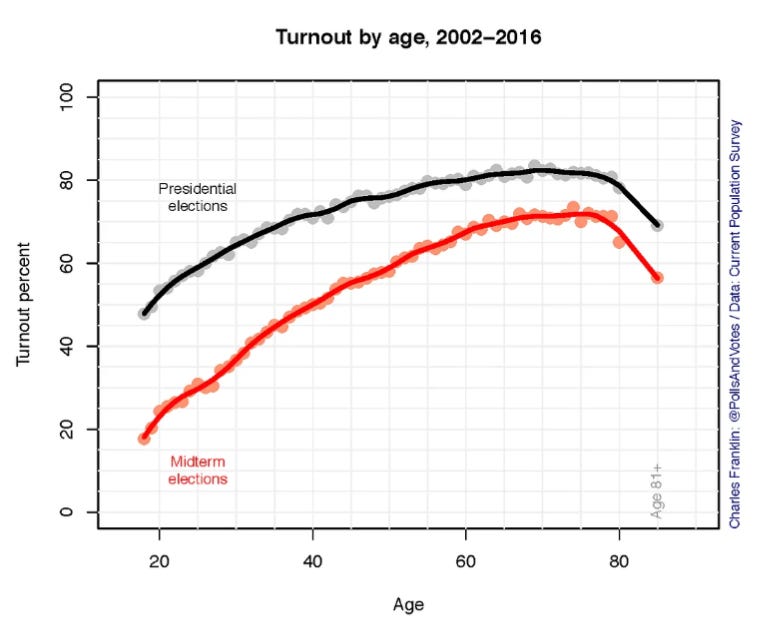

That dynamic is obviously bad for birthrates. Changing it will be politically very hard, especially since the aged have disproportionate political power because they vote such high rates.

So far, few leaders have dared to touch old age entitlements even when it’s clear that a lot of people don’t actually need them. Still, with birthrates in free fall, leaders are needed who can face down the gerontocracy (rule by the old) that grips so many rich countries.

Until then, parents can help young adult children with downpayments, childcare and a lot more. The current paradigm, where people finally see inheritances when they are past sixty, doesn’t help anyone.

Awesome article, will finish reading later...but one question. The charts don't seem to match up. You show that young people's incomes are going down, and you show that they are (now) at the bottom of the pile... but you don't really show that they didn't used to be at the bottom of the pile.

It would be nice to see something more than a tweet as evidence for the age of inheritance.